General (scope, time limits)

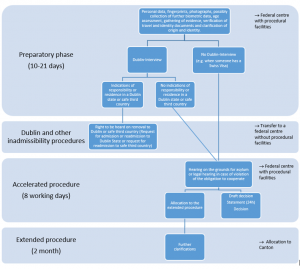

Preparatory phase: The preparatory phase (“phase préparatoire”) starts with the lodging of the application and lasts a maximum of 10 days in the case of a Dublin procedure, 21 days for other procedures. The purpose of the preparatory phase is to carry out the preliminary clarifications necessary to complete the procedure, in particular to determine the State competent to examine the asylum application under the Dublin III Regulation, conduct the age assessment – if the minority is doubted –, collect and record the personal data of the asylum seekers, examine the evidences and establish the medical situation.[1] During the preparatory phase, a first interview is held mainly to determine whether Switzerland is competent to examine the merits of the asylum application (see Personal interview).[2]

On 15 September 2021, the Swiss Parliament allowed immigration officials to access people’s mobile data if it is the only way to verify their identity. The Swiss Refugee Council and UNHCR criticised the measure as disproportionate and an assault on privacy rights.[3] In the context of the asylum procedure, no data from mobile phones were analysed in 2022. A corresponding procedure, according to which electronic data carriers can be analysed during the asylum procedure, is only being developed.[4] At its meeting on 10 March 2023, the Federal Council opened the consultation on the amendments to the ordinance necessary for implementation. The new ordinance provisions determine which personal data on the data carriers of asylum seekers may be analysed by the SEM. In addition, the offices responsible for the analysis within the SEM are designated and the procedure for analysing the data carriers is regulated. Further amendments concern, among other things, the intermediate storage of personal data and the use of software. The provisions also stipulate that the persons concerned are to be comprehensively informed by the SEM about the evaluation. They are to be informed of the possibility of evaluating electronic data carriers at the beginning of the asylum procedure. In addition, the persons concerned are to be informed in detail about the procedure and in particular about the consequences of a refusal to evaluate the data carriers. The consultation will last until 19 June 2023.[5]

Cancellation and inadmissibility decision: On the basis of the findings in the preparatory phase, the SEM decides whether an application should be examined and whether it should be examined on the merits. For inadmissibility grounds see sections on Admissibility procedure, and in particular Dublin.

Dublin procedure: If the preliminary investigations indicate that another Member State might be responsible for processing the asylum application according to the Dublin III Regulation, the Dublin procedure will be activated, for further information see section Dublin: General.[6]

Accelerated procedure: Unless a Dublin procedure is initiated, the accelerated procedure itself starts as soon as the preparatory phase is completed.[7] It lasts a maximum of eight working days[8] and includes mainly the following stages:[9]

- Preparation of a second interview regarding the grounds of asylum;

- Conduct of the second interview and/or granting the right to be heard;

- Assessment of the complexity of the case and decision to continue the examination of the asylum application under the accelerated procedure or proceed to the extended procedure;

- Preparation of the draft decision;

- If negative, legal representative’s opinion on the negative draft decision[10] within 24 hours.

- Notification of the decision

After the interview on the grounds for asylum, the SEM carries out a substantive examination of the application. It starts by examining whether the applicant can prove or credibly demonstrate that they fit the legal criteria of a refugee. As laid down in law, a person able to demonstrate that they meet these criteria is granted asylum in Switzerland.[11] If this is the case, a positive asylum decision is issued.

If the SEM considers however that an applicant is not eligible for refugee status or that there are reasons for their exclusion from asylum,[12] it will issue a negative asylum decision. In this case, the SEM has to examine whether the removal of the applicant is lawful, reasonable and possible.[13] If the removal is either unlawful, unreasonable or impossible, the applicant will be temporarily admitted (F permit) in Switzerland. A temporary admission constitutes a substitute measure for a removal that cannot be executed. It can be granted either to persons with refugee status who are excluded from asylum or foreigners (without refugee status). The scope of temporary admission as foreseen in national law exceeds the scope of the subsidiary protection foreseen by the EU recast Qualification Directive, as it covers both persons whose removal would constitute a breach of international law, as well as persons who cannot be removed for humanitarian reasons (for example medical reasons).

Currently, the duration of the accelerated procedure exceeds the one foreseen in the law. The average time between the asylum application and decision-taking under the accelerated procedure in 2022 was 72 days,[14] while per law it should not be more than 29 days.

According to statistics provided by the SEM in 2021, out of 4,145 decisions on the merits issued within the accelerated procedure, 2,123 (51%) resulted in the granting of asylum and 1,293 (31%) of a temporary admission, while a total of 729 (18%) rejections were issued with a removal order. This suggests that accelerated procedures do not necessarily result in the issuance of negative decisions, as was initially feared by critical observers before the asylum reform entered in force. Statistics on 2022 were not available at time of publication.

Extended procedure: If it appears from the interview on the grounds for asylum that a decision cannot be taken under an accelerated procedure, the application is channelled into an extended procedure and the asylum seeker is allocated to a canton. The switch to an extended procedure occurs in particular when a procedure cannot be concluded within eight working days because additional investigative measures prove necessary[15] or if the maximum length of stay of 140 days in a federal centre is reached.[16] In addition to a possible additional interview, other investigative measures with regard to the identity and origin of the person, the alleged medical problems, the documents submitted or the credibility of the allegations may be taken.

The decision to proceed with the extended procedure is an “incidental decision”[17] that cannot be appealed before the final decision is issued so as to avoid lengthy procedures.

In a landmark decision of June 2020, the Federal Administrative Court ruled that, in light of the different applicable appeal deadlines, a wrong assessment as to whether a case is to be considered as complex or not – and based on which it will therefore be channelled into the extended procedure or not – may constitute a violation of the right to an effective remedy.[18] The Court clarified that a case should be considered as complex and must be channelled into an extended procedure if a complementary interview on the grounds for asylum is necessary,[19] if the applicant has submitted a large amount of evidence or if further clarifications need to be mandated in the country of origin.[20] The extended procedure also needs to be ordered when the deadlines cannot be met, for example when the medical situation of the applicant could not be sufficiently assessed, and especially if the asylum seeker is still residing in a federal asylum centre after 140 days.[21]

During the preparation of the reform, the SEM estimated that approximately 40% of procedures would be conducted under the extended procedure. This estimate later changed to 28%.[22] At the beginning of the reform, however, very few cases were attributed to the extended procedure, approximately 19% of all applications.[23] In 2022, the SEM took 12% of the decisions under the restructured procedure within an extended procedure, 32% within an accelerated procedure and 25% within a Dublin procedure.[24]

Length of procedure: The Asylum Act sets time limits for making a decision on the asylum application at first instance. In an accelerated procedure, the decision should be notified within 8 days following the end of the preparatory phase whereas this period is extended to 2 months under the extended procedure.[25] However, the procedural deadlines set in Swiss law are not binding but rather give a general temporal scope. There are thus no legal consequences arising from not respecting them and no legal action can be taken.

In 2022, the average duration of the procedures (excluding those conducted under the old procedure) from the application to the first instance decision was 67 days for Dublin procedures, 72 days for accelerated procedures and 254 days for extended procedures. These lengths are significantly higher than those foreseen in the law (namely a maximum of 29 days for accelerated procedures and approx. 80 days in the extended procedure). The average duration of procedures that were concluded in 2022 under the old procedure was very high – 964 days.[26]

12,239 applications[27] were pending at first instance on 31 December 2022, of which 104 were still from the old procedure (referring to the asylum system in Switzerland before March 2019) and 248 were applications for re-examination.[28]

The decision-making at first instance should be consistent. Therefore, the SEM coordinates between the six asylum regions. Possible differences could be corrected on court-level, as there is only one – national – instance for asylum cases in Switzerland. However, in practice the jurisprudence of the Court is not always consistent according to the observations of OSAR.

Prioritised examination and fast-track processing

In October 2022, the fast-track procedures were re-introduced[29] for certain countries of origin: Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria[30] and the safe countries of origin (see the relevant chapter Safe country of origin). These procedures are specifically about merging the normally separate procedures of the Dublin-interview and the interviews according to Art. 26 and Art. 29 AsylA in the national asylum procedure for these selected countries. According to the SEM, this should enable the asylum procedure to be completed more quickly.[31]

Under the Asylum Act, asylum applications lodged by unaccompanied minors are examined as a matter of priority.[32] In addition, SEM defines an asylum processing strategy in which it determines an order of priority.[33] In March 2019, SEM communicated its new strategy for processing asylum applications that takes several elements into account, namely (i) the situation in the country of origin, (ii) the credibility of the asylum request and (iii) the asylum seeker’s personal behaviour.[34] Applications that can be processed under the Dublin procedure or under an accelerated procedure are given priority treatment,[35] as well as those lodged by nationals originating from countries with a low rate of recognition. The list of countries considered as having a low chance of success is available online and was last updated in October 2019 (and is still relevant at the time of publication).[36]

Personal interview

The SEM carries out the whole first instance procedure. It is therefore also responsible for conducting the interviews with the applicants during the asylum procedure in both accelerated and extended procedures.

During the preparatory phase, the applicants undergo a short preliminary interview during which they are accompanied by their legal representative. This interview is mainly held to determine whether Switzerland is competent to examine the merits of the asylum application and is called Dublin interview (see section on Dublin: Personal interview).

In case the SEM intends to take an inadmissibility decision (see section on Admissibility Procedure), the applicant is granted the right to be heard, be it orally during the interview or later in writing. The same applies if the person deceives the authorities regarding their identity and this deception is confirmed by the results of the identification procedure or other evidence, if the person bases their application primarily on forged or falsified evidence, or if they seriously and culpably fails to cooperate in some other way.[37] In those cases, there is no second interview.

Unaccompanied minors do not undergo a Dublin interview but are subject to a first interview for unaccompanied minors, during which they are accompanied by their person of trust who is as well their legal representative. The interview serves to gather information about their person, family and journey in order to prepare the next steps of the procedure, which sometimes include an age assessment (see Age assessment of unaccompanied children).

According to the SEM, data on the duration of the interviews is not collected.[38]

Interview on the grounds for asylum: If the SEM declares the application admissible, the accelerated procedure begins and the applicant undergoes a second interview (so-called interview on the grounds for asylum).[39] On this occasion, the applicant has the possibility to describe their reasons for fleeing and, if available, to submit evidence. In addition to the person in charge of conducting the interview and the person who draws up the minutes, asylum seekers are accompanied by their legal representative and, if necessary, a translator. The applicant may also be accompanied by a person of their choice and an interpreter.[40] In 2022, the SEM conducted 6,091 interviews on the grounds for asylum (and 595 additional interviews, see below). The SEM also conducted 19interviews on the grounds for asylum under the old procedure and 30complementary interviews under the old procedure.[41]

COVID-19-measures: The Ordinance on Measures taken in the Field of Asylum due to Coronavirus (Ordinance COVID-19 Asylum), which entered in force on 2 April 2020 and is valid until at least 30 June 2024,[42] allows the limitation of the number of persons present in the same room during the interview.[43]

As of January 2021, interviews mainly took place in large rooms allowing for all participants to attend them in the same room. If one of the participants belonged to a category of higher risk regarding COVID-19 or if there was no such large room available, the interview took place in two separate rooms. On 30 March 2022, the Federal Council repealed the last measures of the Ordinance COVID-19 as of 1 April 2022. The SEM protection concept was lifted on 6 April 2022. Since 6 April 2022, there is no longer a mask requirement in the SEM. The division of the hearings in Wabern into two rooms was abolished. The Plexiglas partitions have been removed. Protective provisions apply to particularly vulnerable persons.[44]

The Ordinance also states in Article 6 that in case the legal advisor cannot participate in the interview due to circumstances related to the coronavirus, the interview can be conducted and is legally effective. This provision has been strongly criticised by the Swiss Refugee Council and other organisations[45] as well as in an academic legal note concluding that interviews carried out without the legal representative are to be considered formally invalid.[46] As a consequence, this provision has not been used in practice, except in a few cases at the beginning of the pandemic.

During the interview on the grounds for asylum, the following main topics are discussed:

- Educational background, training and career paths

- Places of residence in the country of origin and possible stays in other countries

- Family and social environment

- Identity documents

- Itinerary before arrival in Switzerland

- Grounds for claiming asylum

- Pieces of evidence

- Health conditions[47]

Under the accelerated procedure, SEM may subsequently decide to carry out a complementary asylum interview and assign the applicant to the extended procedure if additional investigative measures are necessary. In 2022, the SEM conducted 595 such complementary asylum interviews.[48] This decision is only up to the SEM, however the legal representative can suggest its suitability, for example if not all the relevant topics have been discussed or if they have more questions to add. Interviews conducted by SEM under the extended procedure satisfy the same conditions and requirements as those carried out under the accelerated procedure. In principle, the applicant is invited to an interview, at which they are accompanied by their legal representative. The interview takes place in the federal asylum centre where the first stages of the person’s asylum procedure are carried out.

According to article 17(2) AsylA in relation to article 6 AO1, if there are concrete indications of gender-related persecution or if the situation in the State of origin allows the inference that such persecution exists, the asylum seeker shall be heard by a person of the same sex. This rule also applies to the other participants of the interview such as the interviewer, the interpreter and the legal representative and represents a right for the asylum seeker. Non-compliance with this provision constitutes a violation of the right to be heard. The applicant is, however, free to renounce this right. In this case, a formal right to be heard must be granted. Interviews are also generally adapted for LGBTQI+ applicants, however this is done out of goodwill, it is not a right of the applicant.[49]

In practice, the official in charge of the case may of their own initiative decide to conduct an interview with persons of the same sex as the applicant, or the legal representative may so request. However, it may also happen that this obligation is not complied with in practice, which implies the intervention of the legal representative, who should then require the cancellation of the interview and its conduct with an appropriate interview team composition. In case of male applicants victims of gender related persecution, this provision is implemented in a more open and pragmatic way, asking the asylum applicant which team composition he prefers.[50]

Interpretation

According to Swiss asylum law, the presence of an interpreter during the personal interviews is not an absolute requirement, as an interpreter should be called in “if necessary”.[51] Generally, it is only in exceptional cases that no interpreter participates in the interview. According to the SEM, the interview always takes place with an interpreter, unless the knowledge of an official Swiss language by the applicant is considered sufficient.[52] The SEM issued a code of conduct applicable for its interpreters, specifying their role, the expected impartial and neutral conduct and emotional detachment during translation.[53] The code of conduct has a binding character and is handed over to the interpreters together with the contract. In case of misconduct, various measures may apply, also the ending of the contract. Interpreters are usually recruited by the SEM. The principles of confidentiality are described in detail in the documents «General Terms and Conditions of the SEM Fee Contract» and «Declaration of Confidentiality». These two documents are attached to the fee contract for interpreters and are signed by the interpreters.[54]

Even if, in general, an interpreter is present during the interviews, some problems have been identified with regard to simultaneous translation. Internal, unpublished surveys on procedural problems conducted by the representatives of charitable organisations attending interviews regarding the grounds for asylum in the procedure before 2019 (coordinated by the Swiss Refugee Council) regularly highlighted difficulties relating to simultaneous translation, such as partially incorrect translations, difficulties in comprehension taking into account the cultural context and the corresponding references. In this respect, the systematic presence, in principle, of an interpreter and a legal representative during the interview should reinforce the right of asylum seekers to be able to express themselves in a language of which they have a sufficient command. If significant communication problems arise between the interpreter and the asylum seeker, the interview must be cancelled. In any case, issues related to translation should be mentioned in the minutes so as to be considered by the Court in case of appeal.

The representatives of charitable organisations also pointed out that several interpreters are not impartial, sometimes even have close ties to the regime in the country of origin, or that they lack professionalism (i.e. imprecise, no literal translation but a summary, lacking linguistic competence).[55] Problems have also been identified in relation to the difference in accent or dialect between the interpreter and the applicant, especially in cases where the applicant’s mother tongue was Tibetan, Kurdish of Syria or Dari.

While from time to time there may be a temporary shortage of interpreters for a specific language, it appears, particularly in view of the drop in asylum applications in recent years, that the quantitative needs are generally covered.

Recording and report

Neither audio nor video recording of the personal interview is required under Swiss legislation. The recording of interviews with asylum seekers is a long-standing demand of charitable organizations, which has so far not been implemented by the federal authorities.[56] In a letter of January 2020, sixty-six experts in asylum law requested the introduction of audio recording of asylum interviews, to which the SEM answered vaguely that it needed to examine a series of aspects before considering such a measure.[57]

However, written minutes are taken of the interview and signed by the persons participating in the interview at the end, after a translation back into the language of the applicant (carried out by the same interpreter who had already translated during the interview).[58] Before signing the minutes, the applicant and legal representative have the possibility to make further comments or corrections to the minutes.

Appeal

Swiss law provides for an appeal mechanism in the regular asylum procedure. The sole competent authority for examining an appeal against inadmissibility and in-merit decisions of the SEM is the Federal Administrative Court (FAC, Tribunal administratif federal).[59] A further appeal to the Federal Supreme Court is not possible (except if it concerns an extradition request or detention, including in Dublin cases).[60] If there are to welcome the appeal, the Federal Administrative Court can either deliberate on the merits of a case and issue a new, final decision or cancel the decision and send the case back to the SEM for reassessment. Appeals are usually decided upon by three judges, while manifestly founded or unfounded cases are decided upon by one judge (with the approval of a second judge). Leading decisions (or coordination judgements) are taken by five judges.

An appeal to the Federal Administrative Court can be made on two different grounds: the violation of federal law, including the abuse and exceeding of discretionary powers; and incorrect and incomplete determination of the legally relevant circumstances.[61]

It is important to note in this respect that the Federal Administrative Court cannot fully verify asylum decisions of the SEM.[62] The Court can examine the SEM’s decisions on asylum only regarding the violation of federal law, including the abuse and exceeding as well as undercutting (but not the inappropriate use) of discretionary powers or incorrect and incomplete determination of the legally relevant circumstances.[63] Even if the Court can still verify the appropriateness of the enforcement of removal (as this part of the decision falls under the Foreign Nationals and Integration Act, as opposed to the decision on asylum, which falls under the Asylum Act and is therefore subject to the limitation of the Court’s competence), it is questionable whether the legal remedy in asylum law is effective. The limitation of the Court’s competence in asylum decisions seems problematic and unjustified in view of the rights to life, liberty and physical integrity that are at stake. Also, it can lead to incongruities between the areas of asylum and foreigners’ law.[64]

The appeal must meet a certain number of formal criteria (such as written form, official language, mention of the complaining party, signature and date, pieces of evidence if available). The proceedings in front of the Court should be conducted in one of the 4 official languages,[65] which are German, French, Italian and Romansh. Writing an appeal can be an obstacle for an asylum seeker who does not speak any of these languages. In practice, the Court sometimes translates appeals or treats them even though they are written in English. The Court can also set a new time limit to translate the appeal, but there is no legal basis for this procedure; it depends on the goodwill of the responsible judge. As a service to persons who want to write an appeal themselves, the Swiss Refugee Council offers a template for an appeal with explanations in different languages on its website.[66]

In addition, it must be clear that it is an appeal and what the intention of the appeal is. If an appeal does not meet the criteria, but the appeal has been properly filed, the Court should grant an appellant a suitable additional period to complete the appeal.[67]

The time limit for lodging an appeal against negative decisions on the merits is 7 working days if the decision was issued under the accelerated procedure and 30 days under the extended procedure. As a response to the difficulties caused by the pandemic, the deadline has been temporarily extended to 30 days also for decisions taken under the accelerated procedure (at least until 30 June 2024).[68] No such extension is foreseen for inadmissibility decisions taken without entering on the merit (NEE/NEM), for which the appeal still needs to be filed within five working days. The Court normally has to take decisions on appeals against decisions of the SEM within 20 days in case of accelerated procedure and within 30 days under the extended one.[69] During the 2022, the 20-day deadline was met in 44% of cases (140 procedures). It exceeded by a few days in 23% of cases, by 10 to 30 days in 20% of cases, and by more than 30 days in 57% of cases.[70] Nevertheless, the average procedural duration in front of the Court was 75 days in the accelerated procedure, which constitutes an acceleration in comparison with the average duration of an appeal procedure between 2015 and 2017, that was 159 days.[71] On the other hand, the average duration of the appeal procedure in the extended procedure has risen up in 2022 to 201 days. For Dublin procedures it is 20 days.[72]

In general, an appeal has automatic suspensive effect in Switzerland.[73]

Different obstacles in appeals have been identified. One important obstacle is the fact that the Court may demand an advance payment (presumed costs of the appeal proceedings, usually amounting to 750 Swiss francs (around 755 Euros as of February 2023), under the threat of an inadmissibility decision in case of non-payment. Only for special reasons can the full or part of the advance payment be waived.[74] Appeals filed by legal representatives working for the organisations mandated by the SEM are usually not subject to such advance payment. An advance payment is mostly requested when the appeal is considered as prima facie without merit, which may be fatal to destitute applicants in cases of a wrong assessment. Such wrong assessments have been noted by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).[75] No advance payment can be demanded for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children in appeal procedures.[76]

Finally, the fact that the appeal procedure is exclusively carried out in writing can represent an obstacle since the appellant has no direct contact with the judges and can only express themselves in written form. The Court has the possibility to order a hearing if the facts are not elucidated in a sufficient manner,[77] however in practice, it does not make use of this possibility.

Criticism from UN-CAT: In a decision[78] against Switzerland, the UN-CAT considered that the asylum procedure before the SEM/Federal Administrative Court suffered from significant shortcomings. It stated that the judgment of the Court, given by a single judge, with only an anticipated and summary assessment of the complainant’s arguments, based on a questioning of the authenticity of the documents submitted, but without taking measures to verify them, constituted a breach of the procedural obligation to ensure an effective, independent and impartial examination required by Article 3 of the Convention. Regarding the effectiveness of the remedies available to the person concerned – the appeal to the Court and the request for reconsideration – the UN-CAT notes that the Swiss instances had not applied the suspensive effect to these steps and that the demand for the costs of the proceedings, while the complainant was in a precarious financial situation, deprived him of the possibility of turning to the judiciary to have his complaint examined by the judges of the Federal Administrative Court.[79]

Legal assistance

Asylum seekers have the right to receive free counselling and legal representation at first instance, regardless of the applicable procedure (accelerated, extended, Dublin).[80] This accompanying measure aims compensate the overall aim to speed-up the decision-making process. In order to ensure this legal protection, SEM contracted service providers from recognised charitable organisations to carry out these tasks in the federal asylum centres and at the airports of Geneva and theoretically[81] in Zurich. They are paid based on the number of signed powers of attorney. These organisations were selected through a public call for tenders and all of them have solid experience in providing legal support and representation to applicants. They currently comprise 4 organisations which are present in the 6 federal asylum centres, and their mandate has been extended until 28 February 2023. The organisations are as follows:

| Organisations providing legal assistance at first instance | |

| Federal centre | Name of organisation |

| Altstätten SG | HEKS-Rechtsschutz |

| Bern BE | Rechtsschutz für Asylsuchende (Berner Rechtsberatungsstelle für Menschen in Not) |

| Basel BS | HEKS-Rechtsschutz |

| Boudry (+ airport Geneva) NE | Protection juridique Caritas Suisse & VSJF |

| Chiasso TI | SOS-Ticino & Caritas Protezione giuridica |

| Zurich (+ airport Zurich) ZH | Rechtsschutz für Asylsuchende (Berner Rechtsberatungsstelle für Menschen in Not) |

Source: Swiss Refugee Council, addresses and contacts available at: https://bit.ly/3pYFvVt.

Although mandated by the federal migration authority SEM, independence and confidentiality in the work of legal representation must be guaranteed.[82] UNHCR published a series of recommendations addressed to legal counselors and representatives as well as managers to ensure a legal protection of good quality.[83] The quality of the legal protection was evaluated in an external evaluation mandated by SEM. The results were published in August 2021.[84]

The Coalition of Independent Jurists for the right of asylum, gathering several lawyers and NGOs working on asylum cases, published an independent evaluation of the first year of implementation of the asylum reform.[85] The report partly focuses on the work of the mandated legal protection, pointing to a series of problematic issues. On one hand, the Coalition raises the question of the independence of such mandated organisations, noting that they are very cautious when it comes to taking a stance in the public space.[86] The geographical proximity with the SEM in the federal centres is also reflected in the perceptions of asylum seekers, who do not always take the independence of their legal representative for granted.[87] The report also points at insufficient coordination among the various mandated organisations that have missed, according to the Coalition, an opportunity to jointly influence the development of case law in the interests of asylum seekers.

Each asylum seeker is assigned a legal representative from the start of the preparatory phase and for the rest of the asylum procedure, unless the asylum seeker expressly declines this. The legal representative assigned should inform the asylum seeker as quickly as possible about the asylum seeker’s chances in the asylum procedure. The so-called legal protection in the federal asylum centres, consisting in principle of an advice office and legal representation, mainly carries out the following tasks:[88]

- Informing and advising asylum seekers;

- Informing asylum seekers about their chances of success in the asylum procedure;

- Ensuring the preparation of – and participating in – the interview;

- Representing the interests of unaccompanied minor asylum seekers as a person of trust in federal centres and at the airport;

- Drafting an opinion on the negative draft decision in the accelerated procedure;

- Communicating the end of the representation mandate to the asylum seeker when the representative is not willing to lodge an appeal because it would be doomed to failure (so-called ‘merits test’);[89]

- Ensuring legal representation during the appeal procedure, in particular by preparing and writing an appeal;

- Informing the asylum seeker of the other possibilities for legal advice and representation for lodging an appeal.

In cases where the application is being channeled into the extended procedure, legal representatives must conduct an “exit interview” with the applicant in order to inform them of the further course of the asylum procedure and of the possibilities for legal advice and representation in the extended procedure (see below).

The legal representation lasts, under the accelerated and the Dublin procedure, until a legally binding decision is taken, or until an incidental decision on the allocation to the extended procedure is issued by the SEM. It also extends to a possible appeal procedure in front of the Federal Administrative Court. It ends when the assigned legal representative informs the asylum seeker that they do not wish to submit an appeal because it would have no prospect of success (so called “merits-test”). This can be seen as problematic since the merits-test would be a task for the Court but also, since the estimation of the prospect of success is depending on jurisprudence, the development of the jurisprudence is slowed down. If the legal representative decides to lay down their mandate, this should take place as quickly as possible after notification of the decision to reject asylum in order for the asylum seeker to find another legal representative if wished.[90] The mandated legal representative should give the contact of other legal advice offices.

Revocation of mandates are particularly problematic given the geographic isolation of some federal centres and the short deadlines for introducing an appeal, which can make it practically impossible to find a legal representation and hence prevent the asylum seeker from accessing an effective remedy. This problem is more or less accentuated depending on the region the asylum seeker was allocated to, as discussed above, which also creates unequal treatment. Also, for legal advice offices or lawyers who take over and appeal in those cases, there is only very little time for gathering all documents and writing the appeal.

No statistical data are available on the number of asylum seekers having renounced to legal representation during their asylum procedure nor on the number of asylum seekers having appointed an external independent lawyer. According to the SEM, it is rare that asylum seekers renounce their right to legal representation.[91]

The extended procedure (allocation to a canton)

Following allocation to a canton, asylum seekers may contact a legal advice agency or the legal representative allocated free of charge at relevant steps of the first instance procedure before the decision, in particular if an additional interview is held on the grounds for asylum.[92] In fact, usually there is a change of legal representation after the triage in the extended procedure. However, the legal representative assigned at the federal asylum centre can continue to represent the asylum seeker in exceptional cases if a relation of trust has developed.[93]

Following a public call for tenders, the SEM appointed several organisations active in the cantons to provide legal protection after the asylum seeker’s allocation to a canton.[94] An updated list of all organisations providing legal representation for asylum seekers in the different regions of Switzerland (both those appointed by the SEM as well as other organisations) is available on the website of the Swiss Refugee Council.[95]

The system of legal representation in the extended procedure implemented by the SEM covers solely the decisive steps of the asylum procedure. It does not include the submission of an appeal to the Federal Administrative Court, a task for which they could be reimbursed afterwards by the Court if the appeal is not considered as doomed to fail. Furthermore, several activities traditionally carried out by the legal advice offices active in the cantons do not fall within the scope of application under the new Asylum Act and the related ordinances, for instance family reunification procedures, contacts and reaching out to health professionals or questions relating to accommodation.[96] When asylum seekers are attributed to a canton where another language is spoken than in the one spoken where the federal centre was located, this can represent an obstacle for the legal representative. Complementary interviews will be conducted in the initial federal asylum centre in the language of that centre, and the decision will also be written in that language. A further obstacle for legal representatives in the extended procedure is that the SEM does not allow access to the minutes of the interview on the asylum grounds, except if there is a complementary interview, in which case they only have access the evening (after 17h) before the day of the interview. This time is insufficient to prepare for the interview, especially if it is written in a language that the legal representative does not completely master. This also does not allow for adequate exchange with the asylum seeker, especially when a translator is needed. Nevertheless, it is a little bit better than the old practice, when access was only granted 30 minutes before the interview.

The procedural steps that the legal advisory offices receive remuneration from the SEM for are significantly reduced compared to the accelerated procedure, which means a much lower compensation for legal protection in the extended procedure. To be compensated for the costs of the appeal, the legal representative must apply to the court to be granted free legal representation, which if granted is only paid after the judgment. The only partial remuneration of legal assistance means that in practice, there are steps that are not or insufficiently covered by the compensation received from the state (e.g. the study of files, obtention of means of proof, interpreters, expenses for journeys to see the client etc.). This is especially problematic if asylum seekers are in prison or lodged far away from the legal advisory office (see chapter Detention: Legal Assistance).

[1] Article 26 AsylA.

[2] Article 26 AsylA.

[3] Swiss Refugee Council, Le Parlement restreint encore les droits fondamentaux des personnes en quête de protection, press release of 15 September 2021, available in French (and German) at: https://bit.ly/3q21ZqH; see also the communication of ECRE available in English at: https://bit.ly/3oprHU6.

[4] Information provided by the SEM, 1 May 2023.

[5] Federal Council, press release, 10 March 2023, available in French (and German and Italian) at: https://bit.ly/42f8Ygc.

[6] Article 44 AsylA; Article 83 FNIA.

[7] Article 26c AsylA.

[8] Article 37 (2) AsylA.

[9] Article 20c AO1.

[10] In consideration of this statement, the SEM can adjust its decision. The idea of the statement is that the facts are properly established and that the decision will be correct and comprehensible in terms of formality and in the merits.

[11] Article 49 AsylA.

[12] Asylum is not granted if a person with refugee status is unworthy of it due to serious misconduct or if he or she has violated or endangered Switzerland’s internal or external security (Article 53 AsylA). Further, asylum is not granted if the grounds for asylum are only due to the flight from the applicant’s native country or country of origin or if they are only due to the applicant’s conduct after his or her departure, so-called subjective post-flight grounds (Article 54 AsylA).

[13] Article 44 AsylA; Article 83 FNIA.

[14] Data provided by the SEM, 1 May 2023.

[15] Article 26d AsylA.

[16] Article 24(4) AsylA.

[17] “Zwischenverfügung” in German or “décision incidente” in French.

[18] Federal Administrative Court, Decision E-6713/2019, 9 June 2020. On this jurisprudence see also: Lucia Della Torre and Seraina Nufer, Between Efficiency and Fairness: The (new) Swiss Asylum Procedure, in: Journal of Immigration, Asylum & Nationality Law, Vol. 34 No. 4 2020, 317.

[19] Administrative Court, Decision E-4534/2019, 25 September 2019, para 7.5.1; E-4367/2019, 9 October 2019 para 7; E-4329/2019,7 November 2019, para 7; E-5624/2019, 13 November 2019, para 5.3.2.

[20] Federal Administrative Court, Decisions E-3447/2019, 13 November 2019, para 5.3.2; E-244/2020, 31 January 2020, para 3.7; E-5850/2019, 21 January 2020, para 8.4; 9; D-6508/2019, 18 December 2019, para 5.6.

[21] See for example Federal Administrative Court, Decision E-3447/2019, 13 November 2019 or E-5490/2019, 5 November 2019.

[22] See SEM https ://bit.ly/3WR04mE and also, Swiss Refugee Council, Prise de position de l’OSAR sur l’évaluation externe des nouvelles procedures d’asile, https://bit.ly/3YXfgAw.

[23] SEM, Fiche d’information: chiffres clés relatifs aux procédures d’asile accélérées, 13 July 2020, available in French (and German and Italian) at: https://bit.ly/3EaTRIk.

[24] Data provided by the SEM, 1 May 2023.

[25] Article 37 AsylA.

[26] Data provided by the SEM, 1 May 2023.

[27] SEM, asylum statistics (6-10), available at: https://bit.ly/44rdaeN.

[28] Data provided by the SEM, 1 May 2023.

[29] Following the entry into force of the restructured asylum procedure in 2019, the previous accelerated procedures (i.e. fast-track and 48-hour procedures) were not used anymore.

[30] Aargauer Zeitung, «Die Asyllage ist sehr angespannt»: Bundesrätin Keller-Sutter interveniert bei der EU-Kommission – mit erstaunlichem Erfolg, 15 October 2022, available in German at: https://bit.ly/3l2A368.

[31] Information provided by the SEM, 7 October 2022.

[32] Article 18 (2bis) AsylA.

[33] Article 37b AsylA.

[34] SEM, Demandes d’asile priorité aux procédures Dublin et aux procédures accélérées, 9 May 2019, available in French (and German and Italian) at: https://bit.ly/2u0JQ22.

[35] SEM, Strategy for processing asylum requests: Fast-tracking of unjustified applications, 17 July 2019, available in English (and German, French and Italian) at: https://bit.ly/2uQOaS2.

[36] The list of countries with a low recognition rate is available in English at: https://bit.ly/2Tm0ZOt.

[37] Article 36 AsylA.

[38] Data provided by the SEM, 7 April 2022.

[39] Article 29 AsylA.

[40] Article 29 AsylA.

[41] Data provided by the SEM, 1 May 2023.

[42] Press release of the Federal Council, Coronavirus : prolongation des mesures de protection dans le domaine de l’asile, 16 December 2022, available in French (and German and Italian) at: https://bit.ly/3XbLxkY.

[43] Article 4 of the Ordinance COVID-19 Asylum.

[44] Information provided by the SEM, 1 May 2023.

[45] Swiss Refugee Council, Covid-19 Adaptation des procédures d’asile : la protection juridique doit être garantie en tout temps, 1 April 2020, available at: https://bit.ly/36W9B3e. A more detailed and recent statement of 20 November 2020 can be accessed at: https://bit.ly/2USrAlE.

[46] Thierry Tanquerel, Note relative aux mesures prises dans le domaine de l’asile en raison du coronavirus, 20 April 2020, available in French at: https://bit.ly/3l00Zhc.

[47] Further information about the interview on the grounds for asylum and the quality criteria to be followed by SEM employees in charge of the interviews is available in French in the Handbook of the SEM on Asylum and Return, chapter C6.2, at: https://bit.ly/35WrShA.

[48] Data provided by the SEM, 1 May 2023.

[49] Information by the Swiss Refugee Council, January 2023.

[50] SEM, Handbook on Asylum and Return, chapter D2, 18. Available in French at: https://bit.ly/35UBQAg.

[51] Article 29(1-bis) AsylA.

[52] SEM, Handbook on Asylum and Return chapter C6.2, available in French at: https://bit.ly/3FeHLPJ, 8; Asylum Appeals Commission, Decision EMARK 1999/2 of 27 October 1998, para 5.

[53] SEM, Role of the interpreter in the asylum procedure, January 2016, available in English at: https://bit.ly/2IUogEp; see also SEM, Requirements for interpreters and translators (no date), available in English at: https://bit.ly/3l1nfqQ.

[54] Information provided by the SEM, 1 May 2023.

[55] On the issue of interpretation see in particular: Swiss Refugee Council, L’interprétariat dans le domaine de l’asile n’est pas une question mineure, 5 July 2017, available in French at: https://bit.ly/3lkpv2h and Le Temps des réfugiés, Asile: les superpouvoirs des interprètes; 16 May 2019, available in French at: https://bit.ly/2wIIt9I.

[56] Le Temps des réfugiés, Plusieurs Etats européens procèdent déjà à l’enregistrement audio des auditions d’asile. Pourquoi pas la Suisse?, 4 October 2019, available in French at: https://bit.ly/3c6jFbG.

[57] Jasmin Caye, Auditions : une mauvaise traduction et la vie d’un demandeur d’asile peut basculer, Vivre Ensemble 177, May 2020, available in French at: https://bit.ly/35ZEmFf.

[58] Article 29(3) AsylA.

[59] Article 105 AsylA. Most decisions of the Federal Administrative Court can be found at: http://bit.ly/1NgE8vb.

[60] Article 83(c)-(d) Federal Supreme Court Act.

[61] Article 106 AsylA.

[62] Article 106(1) AsylA. Appropriateness of a decision means situations in which the determining authority has a certain margin of appreciation in which it can manoeuvre. Within this margin of appreciation, there can be decisions that are “inappropriate” but not illegal because they still fall within the margin of appreciation and they respect the purpose of the legal provision, but the discretionary power was used in an inappropriate way.

[63] For a more detailed analysis of the discretionary power of the determining authority and the competence of the Federal Administrative Court, see Federal Administrative Court, Decision E-641/2014, 13 March 2015.

[64] For a more thorough analysis of the changed provision in the Asylum Act, see Thomas Segessenmann, Wegfall der Angemessenheitskontrolle im Asylbereich (Art. 106 Abs. 1 lit. c AsylG), ASYL 2/13, p. 11.

[65] Article 33a APA.

[66] Swiss Refugee Council, Instructions for filing and appeal and Appeal template, available (in several languages) at: https://bit.ly/39cydHU.

[67] Article 33a and 52 APA.

[68] Article 10 of the Ordinance COVID-19 Asylum.

[69] Article 109 AsylA.

[70] FAC, Nouveau droit d’asile ‐ Bilan; 01.03.2019-31.08.2020; statistics available at: https://bit.ly/3pTfLtM; press release of 29 October 2020, available in French at: https://bit.ly/371qeL7.

[71] Information provided by the Federal Administrative Court, 22 February 2019.

[72] Information provided by the Federal Administrative Court, 31 January 2023.

[73] Article 55(1) APA.

[74] Article 63(4) APA.

[75] For example ECtHR, MA v Switzerland, Application No 52589/13, 18 November 2014, available at: http://bit.ly/3HBiT8E. In this case, the Federal Administrative Court delivered an interim decision in which it declined the applicant’s request for legal aid, reasoning that his application lacked any prospects of success. In its preliminary assessment of the case, The Court noted that the applicant was deprived of additional opportunities to prove the authenticity of the second summons and the Iranian conviction before the national authorities because the Federal Administrative Court ignored the applicant’s suggestion of having the credibility of the documents further assessed. It did not follow up on the applicant’s proposal to submit the copies to the Migration Board for further comments, but instead decided directly on the basis of the applicant’s file and his appeal.

[76] Federal Supreme Court, Decision 12T_2016, 16 October 2017.

[77] Article 14 APA.

[78] CAT, CAT/C/75/D/972/2019, B.T.M., 9 December 2022, available in French at: https://bit.ly/3XrB5XA.

[79] § 8.7.

[80] Article 102f AsylA.

[81] In practice, in Zurich, the persons are sent to the federal asylum centre of Zurich after a short security check (information provided by Berner Rechtsberatungsstelle für Menschen in Not, 29 December 2022).

[82] SEM, Asile : attribution des mandats pour le conseil et la représentation juridique dans les centres fédéraux, 17 October 2018, available in French at: https://bit.ly/3936CpN.

[83] UNHCR, Recommandations du HCR relatives au conseil et à la représentation juridique dans la nouvelle procédure d’asile en Suisse, March 2019, available in French at: https://bit.ly/3nQGyFg. Available also in German and Italian.

[84] The evaluation is in German/French available at: https://bit.ly/3f0thru; a comment of the Swiss Refugee Council is available in German (and French) at: https://bit.ly/3tLSiPK. The report found that complex cases are still too often handled in accelerated proceedings. Insufficient clarification of the facts too often leads to incorrect triage. Further, the evaluation found serious deficiencies in every third asylum decision of the SEM, such as insufficient clarification of the facts and procedural errors. Too many asylum decisions continue to be sent back to the SEM for reassessment. According to the figures of the Federal Administrative Court, the rejection rate has decreased from 18.3% (2019) to 11.9% (2020). However, the cassation rate was still more than twice as high as before the system change, when the rate averaged 4.8% for the years 2007-2018.

[85] Ibid, 12, ch. 4.2.6.

[86] Coalition des juristes indépendant-e-s pour le droit d’asile, Restructuration du domaine de l’asile: Bilan de la première année de mise en œuvre, September 2020, available in French at: https://bit.ly/3mJPg7u and in German at: https://bit.ly/34vbKCG, 13, ch. 4.2.8.

[87] Ibid, p. 8, ch. 4.1.6.

[88] Article 52 OA1 and seq.

[89] Depending on the organisation in charge of legal assistance, several steps may have been taken to provide a framework for this sensitive assessment. For example, the principle of double-checking each negative decision received: a manager or more experienced legal officer will systematically evaluate the decision and discuss it with the legal officer in charge of the case. In addition, internal recommendations or guidelines relating to the practice of the authorities make it possible to guide and give clear information to the lawyers in charge of making this merits test.

[90] Article 102h AsylA.

[91] Information provided by the SEM, 1 May 2023.

[92] Article 102l AsylA.

[93] Article 52f(3) OA1.

[94] SEM, Loi sur l’asile révisée : le SEM désigne les bureaux de conseil juridique habilités, 26 February 2019, available in French (and German and Italian) at: https://bit.ly/2TdD2qO.

[95] The list is available at: https://bit.ly/33cXspz.

[96] Swiss Refugee Council, Conseil et représentation juridique, available in French (and German) at: https://bit.ly/3nQiG4C.